“Two weeks? Really? Are you sure? Why?”

We lost count of how many times we heard a response like this from locals while in Glasgow. Apparently spending this long on holiday in Glasgow is pretty much unheard of. It’s more commonly a day trip or quick stopover for the adventurous, bored or directionally challenged vacationers traveling between Edinburgh and the Scottish Highlands. We’re not sure why.

We loved Glasgow. It has fine architecture, lovely parks (more than 90 of them!) and cute neighborhoods brimming with quirk and character but very few tourists. The food was amazing and quite affordable by UK standards. It has a thriving arts and live music scene. It is mostly walkable, but public transit is also easy and cheap. The city has a young and hip vibe: much like Boston, almost a quarter of Glasgow’s population is either a student or employed by one of the various universities. We significantly lowered our own age impact by having Alex join us for a week, which made the whole experience even better.

There are not many (any?) must-see tourist spots in Glasgow, but that’s part of the appeal. There is simply no artifice of pretense here. Most of the museums are free, and there are ancient artifacts casually scattered about in churches, parks and random backyards. A tour guide commented that Edinburgh can turn anything remotely old into a tourist attraction and happily charge 20 quid for entry; in Glasgow, the same object would more likely be used to prop open the door to a pub restroom.

To be fair, Glasgow does have some flaws. The weather we experienced in August was almost perfect, but we know that was an anomaly and might (understatement alert) struggle with the cold, wind, rain and general gloom of winter. And while the West End is generally attractive and well-maintained, there are some rather run-down blocks in the city center, and the natural landscape does not have the stunning beauty of some other places we’ve stayed. But even that has its advantages. The city is generic enough in its appearance to be used in movies as the setting for places as diverse as Gotham (twice), Edinburgh, London and San Francisco. While we were there, it was doubling as Manhattan for Spiderman 4. (You’re just a short drive from the castle used to film Monty Python and the Holy Grail too.)

There was a time when Glasgow could have used a crime-fighting superhero. Glasgow rightly earned its reputation as a dangerous place toward the end of the 20th Century while in the depths of its post-industrial era. Ironically, Glasgow also was voted the UK’s friendliest city around the same time. The running joke was that you would get very helpful directions to the hospital after being stabbed. Only one of those stereotypes still struck us as accurate. We experienced the trademark Glaswegian (a/k/a “Weegie”) friendliness in spades but saw far fewer questionable characters lurking about and heard far fewer police sirens than we’ve encountered elsewhere in our travels.

Oddly enough, Glasgow’s population is considerably smaller now than it was merely 100 years ago. The result is a modestly sprawling city with excellent infrastructure (including the third-oldest subway in the world) that doesn’t feel crowded. Glasgow was incredibly prosperous in the 19th Century as the second city of the British Empire and has the grand buildings and parks to prove it. As we’ve learned to be the case with anything involving Great Britain, much of the money that entered the city was derived from an unsavory combination of the slave trade, colonization and opportunistic industrialization. The accumulation of wealth continued through WWII, as Glasgow was of critical importance to the British war effort. Some of the finest boats in the world and more than 80% of the British naval fleet were built in shipyards along the River Clyde. After the war, the ship builders and the industries that supported them moved to Asia and the local economy went into an extended period of decline.

Due to that history, it’s hard to spend any time in Glasgow without admiring the architecture. Buildings from the early 1800’s feature blonde sandstone exteriors, and buildings from the late 1800’s generally are covered with red sandstone. But there are enough Art Deco, Art Nouveau and contemporary buildings to keep things interesting and even some surviving medieval and Viking-era sites. The University of Glasgow campus is a Gothic Revival masterpiece. We were in awe of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, a leading Glasgow architect and interior designer in the early 20th Century who is considered the Scottish version of Frank Lloyd Wright. We noticed the similarity in their design aesthetic right away but appreciate that Mackintosh was a little more in touch with the practical aspects of his creations.

In its heyday, Glasgow also was at the forefront of scientific and medical research. Think Lord Kelvin, James Watt and the development of antiseptic, ultrasounds and X-Ray scanners. Although macabre by modern standards, one of the most popular pastimes in the early 1800’s was to attend the public dissection of human corpses by medical researchers. On one such day, a physician and chemist named Andrew Ure had the bright idea of attaching electrodes to the corpse of a convicted murder named Matthew Clydesdale and running electric charges through them. This included stimulation of his chest to make it look like he was breathing. Accounts differ as to exactly what transpired next. Clydesdale’s body certainly jolted, and many onlookers claimed that he sat up on the table. Some witnesses testified that his eyes fully opened and he took a few steps before another doctor stepped in and stabbed him in the neck to kill him again. Mary Shelley was known to attend similar anatomy demonstrations and theoretically could have witnessed the Clydesdale event but would have heard about it regardless, as tales about people rising from the dead tend to make the rounds.

The city’s official motto is “People make Glasgow.” That seems like an understatement. Although fun-loving and kind of heart, they are proudly rebellious, liberal and vocal about social issues. The counterculture spirit is captured in the street art, acts of peaceful civil disobedience and a general disregard for authority. It was known as “Red Clydeside” in the early 1900’s because of worker strikes arising from widespread support for communist ideals around organized labor and opposition to Britain’s involvement in World War I. City leaders expressed their opposition to Apartheid in the 1980’s by renaming the street that housed the South African embassy as Nelson Mandela Place. Given that it was illegal to say the name of the imprisoned opposition leader at the time much less have it written on every piece of mail they received, the embassy took the hint and moved to Edinburgh.

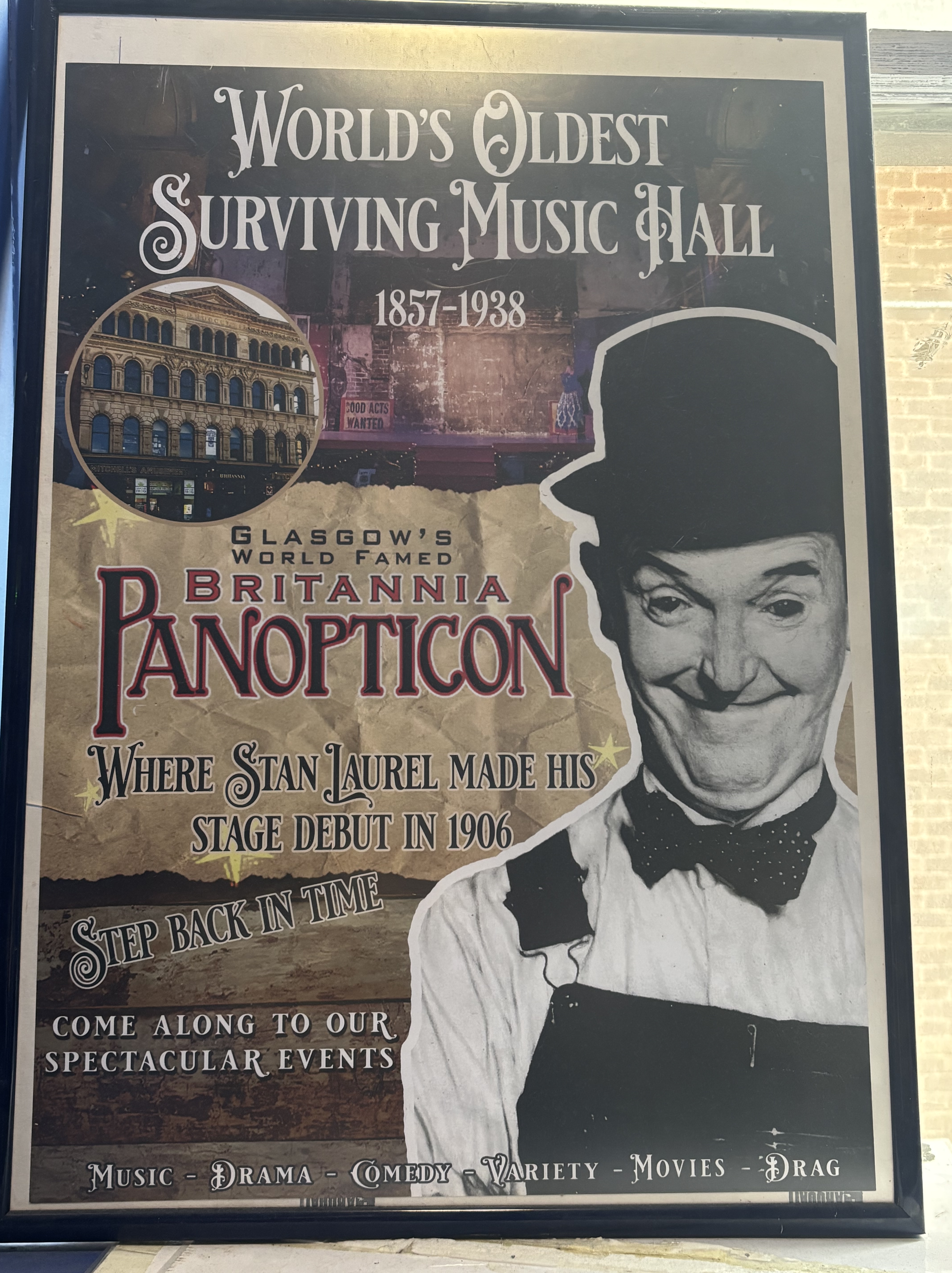

Glaswegians are a notoriously rowdy crowd to perform for if you are a musician. (I suppose it’s to be expected from a citizenry that only a few generations ago liked to electrify corpses for public amusement.) If they like you, they show it. If they don’t, you’ll know it. We visited several historic venues on a music tour and heard quite a few stories about well-known acts being heckled, booed off the stage and even assaulted. King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut is a tiny venue famous for launching bands like Oasis and Blur. The Barrowland Ballroom is considered by some to be the best live music venue in the world due to its unique acoustics. And the world’s oldest surviving music hall – the Brittania Panopticon – was established in Glasgow in 1857. The upper-level balcony was hidden behind a false ceiling for decades until recently being rediscovered by the current owner; the prevailing theory for why it was so well preserved is that it was soaked in so much urine from attendees who couldn’t be bothered to go downstairs.

Without a doubt, Glasgow’s most famous resident is the First Duke of Wellington. Or at least the 200-year-old equestrian statue of him on his horse outside the Gallery of Modern Art in the city center. Weegies began climbing the statute back in the 1980’s to crown it with an orange traffic cone as a practical joke. The tradition continues to this day, with up to 15 cones stacked toward the sky at times and occasionally even a cone on the horse to make it look like a unicorn (which happens to be the national animal of Scotland, perhaps not coincidentally because mythology says the unicorn is the only creature that can defeat a lion, the national animal of England). The city objected for years but finally seems to have conceded the fight now that Banksy has stated that it is his favorite work of art in the UK.

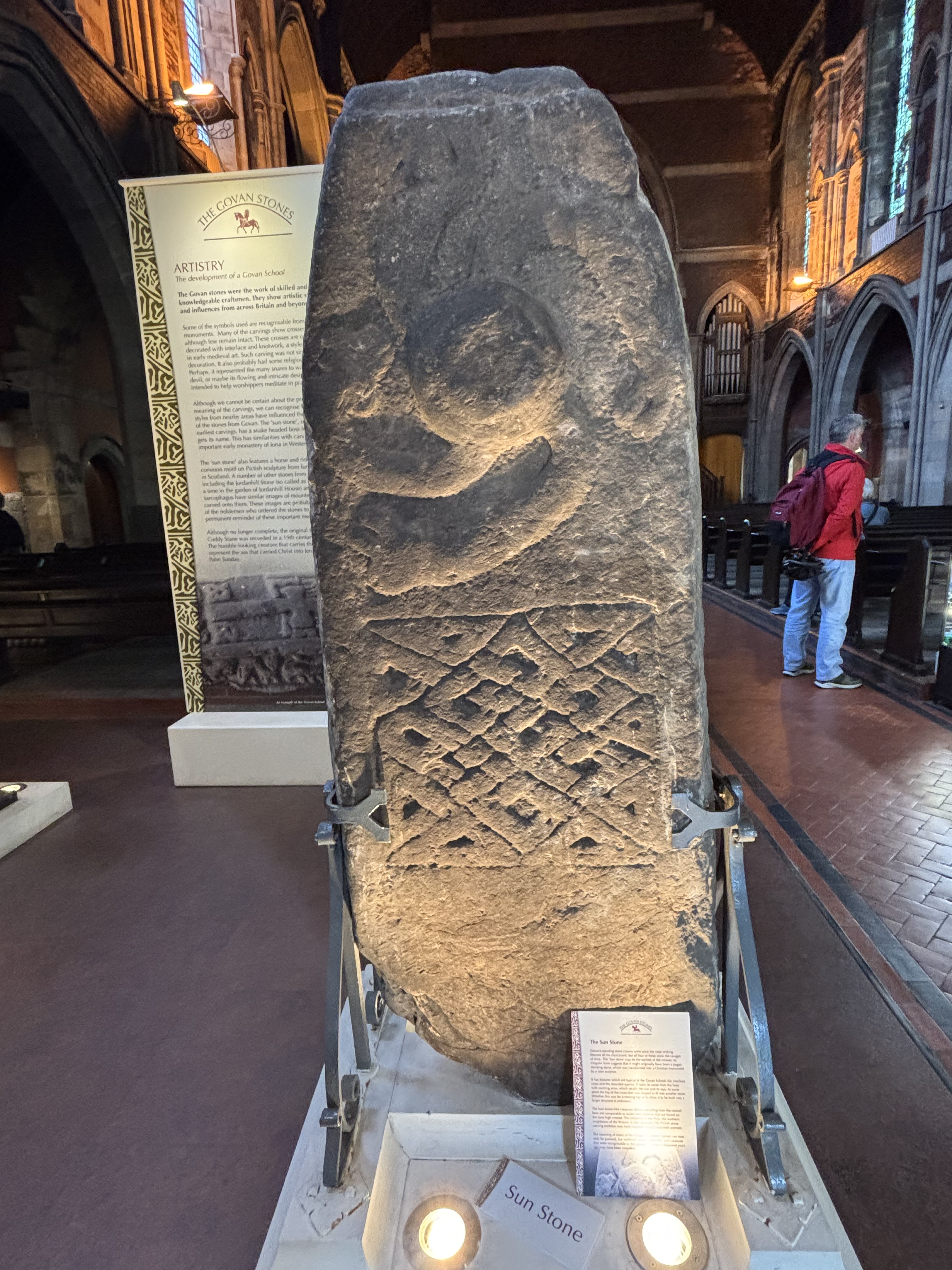

In the end, Glasgow is probably more of a place you live than a place you visit. That said, if you’re here for a short stay (please give it more than a day!), we highly recommend the House for an Art Lover (a Mackintosh masterpiece built decades after his death), the Glasgow Cathedral (uniquely dark due to years of smoke from nearby factories), the Govan Old Church (see Viking hogback tombstones), the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum (the building is as impressive as the contents), the Highland Cattle Park (easiest way to see the adorable “hairy coos” up close), the Once Upon a Whisky West End Whisky Tour (we learned so much that we dare say we’re becoming insufferable whisky snobs), the Gallus Pedals Classic Bike Tour (a great way to see Kelvingrove Park, the University of Glasgow and riverside attractions) and the Glasgow Gander City Centre Walking Tour (including a sample of the famous – but not very good – Irn Bru).

We had too many excellent dining experiences to list them all here, but some of the highlights were Ox and Finch, Ka Pao, Sebb’s, Crabshakk Botanics, Eighty Eight, Partick Duck Club, Stravaigin, Kimchi Cult, GaGa Kitchen + Bar, Tantrum Doughnuts and Nowita Ice Cream. You may get too excited about your meal to remember to take pictures for your blog, but you won’t starve in Glasgow.

One final tip: stay in the West End or Partick and use the subway when you need to travel to the city center. The West End is prettier, safer, less expensive, less touristy and has better food options. The subway is clean, quiet, easy to navigate and cheap. It consists of two tracks running in opposite directions around an oval path (the locals have nicknamed it “Clockwork Orange”), so it’s virtually impossible to get lost. The one downside to the subway is that it appears to have been designed for hobbits, as Stuart hit his head on the door and/or ceiling on multiple occasions. You’d think he’d eventually have figured out to duck upon entry, but you would be wrong.

It’s unclear whether our fondness for Glasgow is due to it being a super-livable city or repetitive cranial trauma, but we’re happy we chose to spend two whole weeks there.

Leave a comment